Dor Does Books

Oh, hai! I read books, then I write down what I think of them.

Dora's ARC - The Sacred Combe by Thomas Maloney

So, this arrived in the post yesterday and I have the first world book blogger problem of beginning it, really liking it, and not having the time to read it.

Samuel Browne's wife has left him suddenly after three years of marriage. She invites him to 'go and live a better life without me'. He must start again, and alone.

And so it is that Sam finds himself deep in the English countryside in a cold but characterful old house, remote and encircled by hills, in the employment and company of an older, wiser man, a man as fond of mystery as he is of enlightenment. What is the purpose of the seemingly hopeless task set for Sam in the house's ancient library? What is the secret of the unused room? And where does a life lose its way or gain its meaning?

The combe is home to a truth born of fraud, a building made of light, and a family wrecked by recklessness: loss and love reverberate around the house and around the novel, providing pleasure, pain and purpose. Combe Hall is a house designed to honour and to enthral. And this very fine debut novel does exactly the same.

Although it's set in the modern day, the writing has a flavour of a 19th Century novel about it, and with the big old house and it's mysterious inhabitants it's got atmosphere in spades. The publishers are making comparisons to The Secret Garden, which is fair.

I'm really quite intrigued by this one. All I need now is to have less to do.

DNF - Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel

I abandoned this one an *age* ago, but I'm also ridonkulously busy at the moment. I don't even have time to procrastinate on Booklikes. *weeps*

So this one is about a post-viral world where a travelling theatre group perform Shakespeare and ... something. Honestly, I'm not that big on post-viral novels for the simple reason that if you've read Stephen King's The Stand, everything else feels derivative. He just did it so thoroughly. It's the same with zombie stuff - it's all The Omega Man with the details changed.

This one split its narrative between the virus taking hold and the 20 years later with the theatre group making their way around the scattered townships which are left. Neither grabbed me. I'm not a Shakespeare worshipper so I'm not really that gripped by the idea of his plays being performed when nothing else is left. I'm sure he's super, and I don't argue with his contribution to language or his general importance, I just say that if you're female or not white, roles become limited. Give me a post apocalyptic theatre troupe who've stumbled across some Days Of Our Lives scripts; that would be interesting story.

I quit about page 100 or so, but I don't rule out trying some of her other books. In accordance with my rules of DNFing, a book which cannot compel me to finish it is unworthy of a higher score: 1 star.

Not what I wanted, but still super readable - A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding by Jackie Copleton

[This book was provided to me free of charge by the publisher Cornerstone, assisted in this awesomeness by NetGalley. I thank them muchly.]

I'm usually leary of books set in countries the author is not from, especially countries like Japan which are so very different from western nations. However, Jackie Copleton's A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding comes with an extremely encouraging pedigree: it was on the Bailey's Prize long-list and Copleton is herself is a graduate of Cambridge and Glasgow, so I had high hopes of this one.

Amaterasu Takahashi survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Her daughter and grandson did not. For almost 40 years she's lived with the guilt of their deaths, until a man with a badly scarred face turns up on her American doorstep bearing a box of secrets. He claims to be Hideo, her grandson, rescued from the ash and debris, then raised by a man Ama would rather forget. To find the truth, she must revisit her memories of days long past, of before the war, and of her belief that everything she ever did was to protect her family.

I didn't care for this book. It's not a bad book, it just didn't offer what I look for. I wanted a book which felt authentic, which told a story I don't know from a perspective completely unfamiliar to me. ADoMU doesn't, not because the author is British, but because it's barely about Nagasaki and its aftermath. Instead its focus is the relationship between Ama and her daughter - Women's Fiction then, which is not always my thing.

Although it opens with this mystery - is the young man at the door truly the grandson Ama believed killed the day the bomb fell? - the question is inconsequential, a jumping off point for Ama's recollections, her diary entries and the papers she is given by the young man. ADoMU covers a lot of ground and consequentially its touches on its subjects are light where I would have preferred a hefty commitment to fewer of them, especially as they were the more interesting (and original) aspects.

If I'd been more caught up in the character, or the writing, I'd feel less short-changed, especially as this book goes down the lazy path so beloved by westerners writing about Japan. I was left very dissatisfied - Ama never feels like an 80-odd year-old Japanese woman. There was no reflection or sense that she'd become a different person at 80-odd than she'd been on the day the bomb fell. The backdrops - of 30s Japan, of Japan at war - felt shallow, never quite coming alive; at one point the local festival of Shoro-Nagashi is described as being "unlike any other in Japan", but the description makes it sound like a variation of Obon. I want to know how it's different, why it's different, and what Ama thinks about it. When she moves to the US, how does it feel to lose this yearly conversation? What was Shoro-Nagashi like the year after the bomb?

There's also least one aspect felt as though it'd been written with Western attitudes in mind, rather than Japanese. I'm not accusing the book of errors (because I honestly wouldn't know), I was just thrown a bit by the suggestion that 16 is young for a relationship in a country where the legal age of consent is 13 (in certain circumstances). It was one of a few small details which contributed to a lack of immersion.

I think it's important to note there's an ongoing background discussion of white voices telling stories which belong to other cultures. This book left me with an overwhelming desire to read something about the legacy of the nuclear bombs by a Japanese writer but Google is bringing me little: everything I can find in English appears to be by western authors. They must exist, surely, but if they're getting translated I can't find them.

A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding is a good book, it just wasn't what I was looking for. I also hope the Bailey's nomination doesn't put potential readers off; this isn't one of those highbrow "hard" reads, it's an interesting one which must surely be a shoe-in for the Richard and Judy Bookclub. The important thing to note is that, despite my complaints, this is one super-readable book and you could do a lot worse when choosing something to fling in your suitcase this summer.

3.5 stars.

1

1

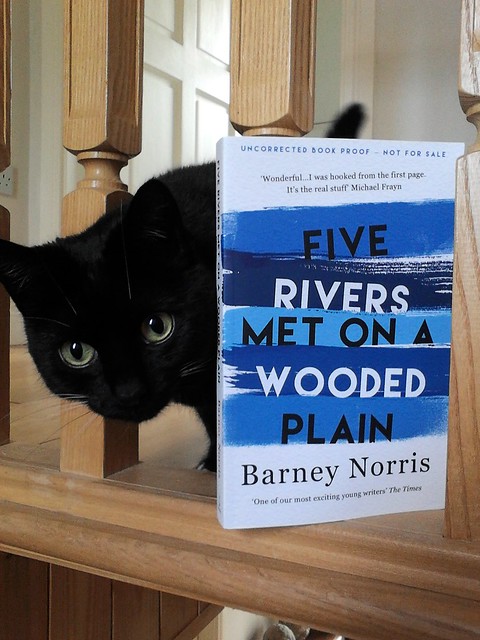

Dora's (Unsolicited) ARC - Five Rivers Met On A Wooded Plain by Barney Norris

My Mammy had her hip replaced on Monday, so I've been bombing back and forth to Kilkenny all week. It's an hour away, and that hour is on twisty roads which require full concentration, so it's been a rather knackering made even more fun by the car deciding to be slightly on fire as we brought her home from the hospital yesterday.

(It's the clutch. We got home by managing to not change out of fourth gear, which in retrospect was a really stupid thing to attempt.)

So, it was really nice to find a postbox surprise from the kind people at PenguinRandomHouse: Five Rivers Met On A Wooded Plain by Barney Norris.

As you can see, Wren is very excited about it too, although not as excited as she was about the prospect of taking a swipe at my head.

Norris is a playwright and the book is set in Salisbury, where I used to change trains a lot and once managed to blag a taxi from the station master because I'd missed my connection.

One quiet evening in Salisbury, the peace is shattered by a serious car crash. At that moment, five lives collide – a flower seller, a schoolboy, an army wife, a security guard, a widower – all facing their own personal disasters. As one of those lives hangs in the balance, the stories of all five unwind, drawn together by connection and coincidence into a web of love, grief, disenchantment and hope that perfectly represents the joys and tragedies of small town life.

Also in ARC mentions is a book I've just finished, A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding by Jackie Copleton; a review is forthcoming and I say it's quite good.

So, that's my week. Hope everybody is doing well. :D

3

3

Of course I will - Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock by Matthew Quick

If you recognise the name on the cover of this one, it's because Matthew Quick is the author of The Silver Linings Playbook, and if you've only seen the film, it's worth noting it managed its topic far less well than its source material. Where the film sometimes got uncomfortably close to laughing at people with mental health problems, the book didn't, so discovering that Matthew Quick makes a habit of writing about characters with mental illnesses does not fill me with dread and horror.

Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock is the story of the eponymous narrator's 18th birthday. He knows exactly how he's going to celebrate: he's going to thank the only four people in his life who've made a difference, then he's going to shoot his former best-friend Asher, then he's going to shoot himself.

It's difficult to feel sympathy for Leonard. He's very much of the privileged, Holden Caulfield, poor-little-rich-boy school of characterisation. He is intelligent (leading to a degree of obnoxiousness), and entitled, and he has the freedom (and money) to do what he wants. With his mother practically living in NYC, he can spend the day watching Bogart films with his next-door neighbour, or skip school to spend the day stalking adults as "training" for real life.

However, what saves this is Quick: a good writer who understands his character. From the off Leonard is asking to be stopped. Where Quick's best known protagonist Pat Peoples was earnest and straightforward, Leonard operates at full subtext, desperate for somebody to realise what's happening, what has happened, and prevent anything further. He's somebody who's slipped through the cracks opened by the limits of polite social discourse.

And so the book proceeds through Leonard's birthday, to the people who've meant something to him and his private desperation for one of the them to realise what's going on.

It took me a while to get into this book.

Leonard's narration tends to paragraphs of a single sentence.

I stuck with it because Leonard is supposed to be 18 and I assumed it was a deliberate stylistic choice.

It was irritating to begin with, though.

Really, really irritating.

The text is littered with footnotes. Footnotes on a Kindle are a nightmare and it was for this reason I got a copy from the library rather than buying it.

There were also these bizarre 'letters from the future' - the first from Leonard's colleague of 20 years hence who explains the world is now a flooded wasteland and they tend a lighthouse. The first of these threw me so hard out of the book I skipped it, only returning later once I'd got a firmer grip on things. Once I understood what these passages were, I thought they were great.

I love books which drive inexorably to their conclusions; I love the tension of trying to avoid a pre-determined outcome far more than a general 'what happens next?'. Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock is tremendous in this regard, the way it focussed on Leonard, on the damage his own actions and his own plans cause him. It doesn't excuse him or explain it away; reasons are given as much as reasons can be. He perpetuates the damage he's been dealt.

Although it sounds quite hopeless, it's not. It has a peculiar lightness to it, the relief of a decision made which is going to be carried out.

Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock is one of those books I wasn't sure about while reading it, but as a whole it's great. The more I think about it, the more I like it and I'll likely be giving it a reread at some point in the dim and distant future (although not on Kindle, due to the footnotes).

4 stars.

A book ill-served by its cover - The Death House by Sarah Pinborough

One of my pet hates is books which are misrepresented by their covers and blurbs. A book cover is a visual language. It tells the ideal reader THIS is the book they want to read; THIS is what their life has been missing. It tells them about the others books they've enjoyed and lets them know THIS book is going to be just as good, MAYBE BETTER. Misrepresentation only leads to tumult of poor reviews from those expecting something distinctly other than they got.

Sixteen-year-old Toby lives in The Death House with the other Defectives. Presided over by Matron and her team of nurses, the children of the house are watched carefully for symptoms of their illness - a runny nose, shaking limbs - when they will be taken upstairs to the sanatorium. Nobody ever returns.

From the blurb, the cover and the title, I could be forgiven for expecting something sinister and creepy. Instead, I got a largely gripping young adult novel which had me initially pleased it had been so badly represented (because otherwise I wouldn't have picked it up).

The Death House begins with the arrival of new Defectives to house, including the rare spectre of a girl: Clara, who has red hair. Where Toby is angry - at his role as patriarch to the younger kids in his dorm, at the theft of his life - Clara is bright, like her red hair, vibrant, like her red hair, and a source of annoyance to the despairing teenager. The previously divided community is mended by red-headed Clara's manic pixie dreamgirlish red hair, the older boys playing nicely with each other in an attempt to impress her.

Which is what this book is, really: a love story about children who are having to cope with their imprisonment and imminent death. I find I like the idea of it more than I ultimately liked the book. What's there is kind of shallow, and repetitive. I can think of other books which do this far better.

I think what frustrated me the most was the lack of worldbuilding. By the end I was reading madly, eager to find out more about the world, but I was to be left disappointed. The sci-fi/dystopian/whatever-you-want-to-call-them elements of the book play a firm second fiddle to the emotional story of the characters. This can be done well - think of Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go - but where Ishiguro drip-fed specifics to allow an understanding of his world and how it worked, Pinborough doesn't bother. The Defectives are never explained. What they are, what they will become, the place of The Death Houses in UK society ... all remains unexplained. I'm guessing when I say this follows Ishiguro's lead in being an alternative world rather than a near-future-dystopian.

In Never Let Me Go, there is a reason for the house the characters are brought up in - it's the sort-of the point of the book - but with Pinborough's Death House, I just wonder why anybody would bother with this set-up. Why make a pretence at continuing their education? Why not just euthanise them? The question is touched on but so indirectly that I wonder if the answer is Pinborough's or mine.

Clearly The Death Houses are a Thing in Toby's world - on the day he is taken he notices the empty streets, only appreciating why when he is ushered into the van waiting outside his house - yet he offers no information about them. Another character indicates there are several of the houses around the country, so it's not as though it's only a dozen children a year who are found to be Defective. What place do they occupy in this world? By concentrating on the love story, Pinborough has abandoned lore to an annoying degree.

Then there is Matron, the faceless autocrat, whose eye the children avoid drawing lest they find themselves come for in the night. She is ridiculously two-dimensional. Without any wider context, I'm again having to make guesses why she makes the decisions she does and really, the best I come up with is stupidly over-simplified.

Overall, I sort of enjoyed it. The Death House is a fast read and one I stayed up to finish, but in the end what it offered was not what I wanted, nor what I enjoy. I honestly don't know why this isn't marketed as Young Adult, unless it's because this is a British book which involves British teens doing what I, obviously, was far too well brought up to engage in at that age. I'd cautiously recommend it, but you may be left feeling unsatisfied.

3.5 stars.

Jane Eyre stars in Gone With The Wind in India - Zemindar by Valerie Fitzgerald

Laura Hewitt has no great desire to accompany her cousin Emily to India, not least because Laura is slightly in love with Emily's new husband Charles. Even so, she's fascinated, desperate to see the 'real' India, and eager to learn everything she can about the country. With Emily and Charles, she journeys from Calcutta to the estate of Charles' half-brother, Oliver Erskine, the fabled Zemindar who runs his land as his own private fiefdom. But with mutiny and war stirring, will any of them remain safe>

Although slow to get going, Zemindar is initially fascinating. The slow progress from ship to land to country gives a tour of the British Raj. It's largely the type of thing you'll find elsewhere - all the usual characters are here, from the Ladies Who Maintain The British Way, to the Faithful Indian Servent - but touched with moments I suspect Fitzgerald may have drawn from her own family history. It is these details which make the book worth reading - the first-hand accounts characters give each other of what they have witnessed. I only have a broad general overview of this period of history; I found the details of life in India at that time hugely interesting.

In many ways, Zemindar is like Gone With The Wind, and not just for the overload of historically appropriate casual racism/colonialism. There's a fairly generous mirroring of a number of GOTWs plot points but thanks to the powerfully written backdrop this is less of an issue than it might otherwise have been. Unfortunately, the second half is just so ... very ... boring.

The meat of the story lies in the siege of Lucknow, when the Brits hole up in the Governor's residence to defend against the rebelling populace. It's an astonishing story in many ways, but one which could have likely been done justice in fewer than 400 pages. While there are plenty of engaging - and horrific - bits, there are also enough dull parts for me to have gone away to read something else at 85%, then had to really force myself to come back to finish it. At 89% I went and looked up the Siege of Lucknow on Wikipedia, realised there were still weeks of the damn thing to go, and almost quit again. It wasn't just the romance, of which I am not the greatest fan anyway, but the limited amount of things which can happen while everybody was sitting around with very little food for 6 months.

I persevered, mainly because when I've read that much of such a long book already I'm determined to get to the end. It wasn't worth it. The romance elements come together in the way of a book which has a single loose end to wrap up and is determined to get it done quickly. The challenges facing the characters were good (and interesting) ones, but the resolution was desperately weak.

Zemindar was originally published in 1981 - it's recently been rereleased by UK house Head of Zeus - and I feel it bears the scars of that. It has more in common with those epic doorstops of the time such as M M Kaye's The Far Pavilions and James Clavell's Gai-jin (which I cite rather than Shogun because it's the only one of his I've read). I, however, judge it as a modern reader and my judgement is that the one this this world doesn't need is a reprint of yet another book starring a plucky woman of the British Empire showing how completely un-racist she thinks she is in other peoples' drawing rooms. There are plenty of books which do this sort of thing no less problematically to my modern eye; why resurrect this one?

While I enjoyed the first half and got through it quickly, largely because I'd put my back out and couldn't do anything else but read, the second half was dull and the last 20% as boring as a large piece of apparatus designed for such a task. Thanks to its length you get your monies worth long before it becomes so and for that reason alone I won't steer anybody who loves the aforementioned books away from it, but don't feel bad if you quit before the end.

1.5 stars.

12

12

With extreme Prejudice - Longbourn by Jo Baker

I am not the biggest fan of Jane Austen. She feigned illness to avoid my namesake (true story) and my family has harboured a grudge against her ever since.

Longbourn by Jo Baker is a companion novel to everybody-but-me's favourite Austen novel, Pride and Prejudice, and follows the main narrative of that book from the point-of-view of the Bennett's housemaid, Sarah.

The first test of a book like this is always whether it's doing more than hitching to the coattails of a classic text. Lynn Shepherd's are an example of when it doesn't. This does, although at times in a rather heavy-handed way, the scrubbing of Lydia's petticoats upon her triumphant wedded return to the house being a particular example. But it also sheds new light on the wider context of P&P, which I - in, I freely admit, ignorance - had never thought to apply: the Napoleonic wars crop up, giving the dastardly Wickham's character another blow; there is the source of Bingley's fortune.

It's own story, a romance with a light sprinkling of social commentary, is pleasing enough should you care for that sort of thing. I don't usually and, as a result, found the end as meh as I find almost all romances.

Those who've never read P&P, or seen the film, or the BBC translation, are unlikely to find much here. Those who are fans of P&P may find themselves bored when the book takes itself away to its own storyline. Scholars who enjoy Austen for her wit and cynical take on society will find such aspects absent. I liked it well enough, but I would be more interested to read something by Baker when she is unhindered by adherence to a concept.

3 stars

9

9

Raise money for RAINN, laugh at Theodore Beale

You may or may not be familiar with the name Theodore Beale. He is also known as Vox Day. Tl;dr version: he's not keen on women's rights and was kicked out of the SFWA for calling N.K Jemisin 'an educated, but ignorant half-savage'.

Blogger Natalie Luhrs has a copy of one of his books. For every $5 raised for RAINN (or, as she mentions in the comments of her blog, for your own local charity doing similar work) she will livetweet one page using the hashtag #readingVD. If she raises $2000, she'll read the whole. damn. thing.

Her blog post with details of how to register your donation to the official count is here. Her Twitter is here.

She's already up to $825. The read has BEGUN.

Spoooooooky - The Woman In Black by Susan Hill

I've read - and, I will admit, been slightly underwhelmed by - Susan Hill's other ghost stories, The Small Hand and The Man In The Picture. It's not that there's anything wrong with them, more that there's something right and in achieving that, the stories became slightly too familiar, slightly too much like the traditional ghost story or folk tale for me to enjoy. The Woman In Black is Hill's first and best known attempt at the genre.

It echoes the traditional structure of the English ghost story: at Christmas, by the fire, tales are told. But Arthur Kipps has a tale he will not tell, not to his step-children or his wife; a true one, of something which happened to him years before as a young man, something from which he has never truly recovered. A story of his time at the remote Eel Marsh house, and of the woman in black.

It's a well written story which nicely emulates the style of M R James, creeping rather than shocking, a sense of dread rather than a sense of horror.

However, it's to this book's detriment that I've seen the film adaptation of it. Although they have a number of significant differences from each other, much of the meat is identical. Unusually, the film fleshes out the story. What's here is simple with the neat, fatalistic approach expected from the genre, but I found myself missing the impetus of screen-Kipps.

If I hadn't seen the film, I may well have enjoyed this more. As it is: 3 stars.

9

9

Mario of Thrones

Once upon a time an absolute genius decided that what the world really needed was a map of Game Of Thrones' Westeros recreated using the sprites from Super Mario World. NESteros was born (although strictly speaking it should be SNESteros).

Then, a further genius took the time to turn it into a cross stitch pattern and made it available for all the world to use.

Then I had A Moment.

Because it's 300-odd stitches by 600-odd stitches, I thought it would be best done on 28 count evenweave over 1 thread. Which is teeny - the stitched area is about 11 inches wide. And as it turns out, I vastly overestimated my ability to see things that small. It's going to look brilliant because the tiny stitches replicate the effect of the pixels, but it's also sending me blind.

What this picture doesn't show very well is all the slightly off-white stitches in the top bits (I am *never* stitching *anything* on white fabric *ever* again) nor the fact it's got a few discoloured patches because I keep sewing cat hair into it. However, I don't care because it's going to be epic. In at least 2 years time.

So, that's what I've been up to.

Hmmm - Foxglove Summer by Ben Aaronovitch

Although I like it, Ben Aaronovitch's Peter Grant series has been a bit hit and miss. The first, Rivers of London, was an absolute stonker - think Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere as a police procedural. The second, Moon Over Soho was slightly dire but managed to redeem itself with a lively final third. Book three was better, book four a bit better than that (provided you have my interest in urban architecture). Foxglove Summer, the fifth entry in the series, is no worse than the previous two.

London copper and apprentice wizard Peter Grant has long since learned not everything is as normal as he used to think it was. This week he's learning that The Folly, the supernatural branch of the Met, takes an interest in missing child cases, just to be sure they haven't been spirited away by anything Grant will only find out exists now. So when schoolgirls Nicole and Hannah leave their beds in the middle of the night, Peter's off to the countryside to interview an old acquaintence of Nightingale's, just to be sure there's nothing 'Falcon' going on. And since he's already out there, Peter volunteers to help the West Mercia Police with their investigation, an offer the overstretched rural force is keen to accept - and not just to show the doorstepping national press that yokels can do diversity too.

The strengths of the series are intermittently out in force: the fun to be had from somebody trying to negotiate the line between getting the job done and filling the paperwork out afterwards; the blending of traditional folklore with the series' rather more modern take on it (high fives for diversity and a pointed look at every fantasy author who's proffered excuses for the majority of white maleness in their books); some great back-and-forth dialogue; and although it's slow in parts, especially at the beginning, when the story *is* moving it's so terrific I risked hideous sunburn to continue reading.

But the weaknesses are there too, especially Aaronovitch's continuing inability to write a convincing relationship. I'm not looking for great romance here, I'd just like a sense of what either of them see in the other beyond a keenness to get carnal. A supernatural moment between the two is incredibly unpleasant but because of the simplistic way we view men as creatures whose interests begin and end with whether they get to have sex or not, it's written in a positive light.

It's frustrating because Peter's laconic narrative doesn't preclude emotion. There is a moment with a tree which is so perfectly done, which shows the underneath parts of Peter so much more effectively than his articulating them would do, that it becomes all the more frustrating for it be placed alongside a relationship which is little more than brief descriptions of energetic lying down.

I'm also having problems with the world building. Each book brings new ideas, often very good ones, but I sometimes feel it's at the expense of developing those already established. And while Foxglove Summer does give some series arc related insights and hints of things to come, those aspects remain very much a sub-sub-plot. I don't feel like we're moving towards a predetermined idea in which all the pieces will suddenly come together and have me scrambling to re-read the series.

While I really liked the premise, the whole thing felt under-done. Removing Peter from London gave some freshness, but not quite enough. The ending itself is horribly rushed, to the point that I feared a cliffhanger approaching. There wasn't, but that would almost have been preferable.

I do like this series and I will certainly be reading the next one, but despite this I can't recommend it (beyond the first book). If you don't like what's gone before there's nothing here to change your mind, but if you do like it this is engaging, occasionally tantalising, and hugely frustrating in equal measure.

3.5 stars

7

7

My sister, the Zombie

She's the one in the duck-egg coloured t-shirt. :D

There's famousness for you, isn't it?

This is what happens when it's carefully explained to Anne Rice what's wrong with supporting *that* book

Tl;dr version:

Poster: *simple explanation of what's wrong with the book.

Anne Rice: CENSORSHIP IS MORE WRONGER.

The censorship I believe she's referring to is the whitewashing of Jefferson as a really great guy who didn't rape slaves. Which is now a 'relationship'.

I can only assume that when she says 'Everybody counts, or nobody counts', she's believes in the second option. I'm not seeing Sally Hemmings counting for much in her side of the conversation.

Calling out the erotification of a documented rape: now the same thing as trying to have works by LGBT authors banned. What next? Paedophilia is just another fetish? In the future it will be completely legal?

Everybody has their own point where they just want a plug-in to turn all mentions of Rice into kittens. This is mine.

Oh God, Why? - The Selection by Kiera Cass

The Selection by Kiera Cass is not my sort of book. I'm not a big reader of YA and when I do, most of it I don't care for. But this was free on Amazon UK, and I'd just finished The Fellowship of The Ring and was at the point where any more Tolkein would make my brain melt, so this felt like a great idea.

Which is was. To begin with.

There will be what are technically spoilers, but since nothing actually happens book which couldn't be predicted by the blurb, it's not actually going to matter. It's also the first (and likely last) gif-based review I've written (which you may need to look at the blog page itself to see, rather than just reading in your dashboard.)

I'm so, so, sorry.

The Selection is set in the futuristic dystopian land of America, now the monarchy of Illea which is ruled by the Good King Clarkson.

Obviously, this means its people are horribly oppressed. They have a caste system which determines your job and your prospects. Eights are homeless beggers. Ones are royalty. Our heroine is America Singer, a Five. Three castes from the bottom. Fives are artists and entertainers because, obviously, art and entertainment are useless commodities which are therefore done by a low caste.

But, yannow, this is teen fiction. For teens. Teens don't need logic or credible world building. They're not even going to notice that even though Fives are supposed to be a low caste they can still become rich and famous for their art like America's brother does. I'm not sure why America doesn't aspire to become a famous singer who can earn lots of money for her family, but it's probably something to do with having no positive female role models in her life.

Anyway. Illea is a nation under threat. Some years ago, due to some unpaid debts, the proud nation of America was invaded by China. China won.

The USA became the ASC, the American State of China. Russia invaded but happily, the Chinese were cross about it and attacked Russia too. Logic happened and America became the kingdom of Illea. There should be an accent over the e, but I'm somewhere between lazy and stupid so I'm not bothering.

These days, King Clarkson rules a land threatened by invasion on all sides and by at least two groups of rebels on the inside. He has a son of marriageable age. In Illea, the crown prince marries a commoner to show solidarity. 35 girls are chosen by lottery to go and be Prince Maxon's harem until he chooses one to be his missus. It's not sexism because Maxon doesn't have a choice either.

America doesn't want to be the bride of Prince Maxon. She wants to marry her Six boyfriend Aspen. He's great. He's 'thin, but not too thin'.

He insists that she apply to be one of the Selected because he couldn't live with himself if he denied her the opportunity to become Queen. She does. He then has a massive hissy fit because she earns her own money and buys him dinner. Then he breaks up with her.

So America applies and, amazingly, she's chosen. She doesn't want to be Queen or marry Prince Maxon, obviously. She's busy being broken-hearted because she wanted to marry Aspen and have his babies and be a cleaner like him, but - le sigh - her family will be paid while she's having fun at the palace so it's her duty to stay there as long as possible so they can have food and stuff.

She goes to the palace where the first step is to get a makeover and get featured on a TV show with the other contestants. It's just like The Hunger Games but without the armpit hair and the training to put pointy things in other peoples' heads. Anyway, America doesn't get much of a makeover because she wants to still look like herself. Luckily she's really beautiful. We know this because she gets told. Repeatedly. Then she says she isn't so people then insist she is. So, yeah, she's just looking like herself and everybody loves her because she held everybody up at the airport talking to plebs, oh and she's beautiful. The other girls in the selection are dressing to entice Maxon, but it doesn't work because America's dressing like she normally does and it turns out she's beautiful.

How you look is the only thing which matters. Don't worry about your personality, or your knowledge of politics, or your life skills, or any of that crap: how you look is the only way to net a man and it's the only desirable quality in a Queen. I'd always thought the ability to eat 'local delicacies' without vomiting into the lap of your neighbour was the kind of skill you need for that job, but what do I know.

Luckily, America is very beautiful. Wait, did I mention that? Never mind: it always bears repeating. America is very beautiful and Maxon fancies her immediately and asks if she thinks she could ever feel the same. America's known him for all of ten minutes so she knows that she couldn't, plus there's Aspen who's broken her heart 4eva, but, yannow, her family, so she offers to be Maxon's spy on the inside. She's going to feed him information about which of the other girls would be a great Queen for him.

After which point, this book becomes very disappointing. Initially, The Selection is definitely 'so bad it's good' territory. It's stupid, but wonderfully so. The only explanation for its publication is that everybody involved has nothing but contempt for anybody under the age of 14. The problem lies in the fact that nothing happens. You don't need to be a genius to realise America is going to fall for Maxon, nor that Aspen is going to make a reappearance and America will be torn between the two of them. Unfortunately that doesn't happen in this book. The Selection ends at the first stage of The Selection process, with the 35 girls whittled down to 6. America knows she's going to be one of them because she's extracted a promise from Maxon that she would be and this never feels realistically in doubt.

Cass tries to inject some drama into the book's second half with some rebel attacks so traumatic some of the girls faint, want to go home, then change their minds, but it's so very tedious. It gives America a chance to show what she's made of but unfortunately she's made of not fainting, closing shutters, and taking a neo-colonialist attitude towards her maids. You're not a hero when you treat people like property.

There are not many books which are as actively offensive as this one. I can understand why some might like it but I found it utterly repugnant. It's not just the content, it's the construction of it, a cynical exercise in exploiting what is seen as a hugely lucrative market. It's an ignorant and harmful perpetuation of negative female stereotypes. It's not even good enough to hate-read.

I know I'm not the audience for this book but frankly, I really hope anybody who thinks they are realises they're better than that.

3

3

1

1